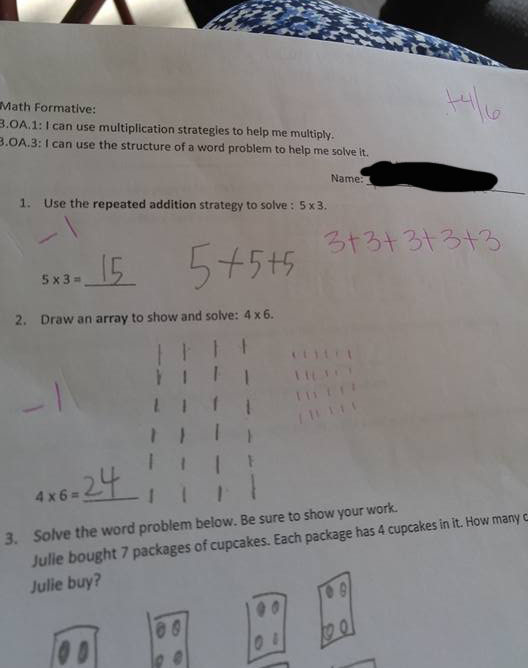

I recently saw this image, taken from a maths test.

The student has been asked to represent 5×3 in terms of repeated addition. They have written 5+5+5. The teacher has marked this as incorrect and given 3+3+3+3+3 as the correct answer. Like many people, when I first saw this I thought the teacher was clearly wrong. After a bit of thought I realised they were correct, and after still more thought I realised this question raises a whole lot of interesting points.

So why isn’t 3×5 the same as 5×3?

First we must define what it means for 3×5 to be the same as 5×3. One answer is that we can substitute one expression for another with no observable change. That is, wherever we see 5×3 we can write down 3×5, and vice versa, and there is no change in meaning. This requires us to define what is “observable”, or what an expression “means”. The usual approach is to define meaning as the result that expressions evaluate to. Under this approach the expressions 3×5, 5×3, and 15 are all equivalent because they evaluate to the same value, namely 15. But as programmers we know that this model does not capture all aspects of meaning. For a very concrete example let’s switch to considering sort algorithms.

You’ve probably studied sort algorithms at some point. There are many sort algorithms that if considered only in terms of their output are all equivalent—they all sort their input! But a basic part of studying them is learning that they are not equivalent along other dimensions. For example, bubble sort has O(n2) complexity in the average case, is stable, and can run in-place. Quick sort has average case complexity of O(n log n), is in-place, but is not stable. Merge sort has average case complexity of O(n log n), it is stable, but it is not in-place. These are a just few of the properties we can consider. We could also look at worst-case complexity (quick sort’s is O(n2)), ease of parallelisation, locality of reference, and many many more.

There are two key points we should take from this: there are many different properties we can derive from an algorithm, expression, or other computational object, and if we treat our computational objects as black boxes we cannot derive these properties (except, perhaps, experimentally).

Let’s return to considering 3×5, 5×3, and 15. They are all equivalent under what we might call the standard interpretation. That is, they all evaluate to the same value. But there are other interpretations where they are not equivalent, such as the number of operations each expression requires. Let’s write some code to illustrate this.

Our first step is to decide on a representation for expressions. In the exercise the student is asked to represent multiplication as repeated addition, so 3×5 becomes 5+5+5, for example. We are only going to deal with addition and integers, so we can express everything of interest using just lists of integers. For example, 5+5+5 can be represented as List(5,5,5), and 15 as List(15).

With this representation it is clear that 3×5 is not equal to 5×3.

val threeTimesFive = List(5,5,5)

val fiveTimesThree = List(3,3,3,3,3)

threeTimesFive == fiveTimesThree

// res: Boolean = false

We can evaluate our expressions under the standard interpretation and show they do evaluate to the same value. Therefore substitution is maintained and the two expressions are equivalent under this interpretation.

// The short way

threeTimesFive.sum == fiveTimesThree.sum

// res: Boolean = true

// The longer, more explicit, way

threeTimesFive.foldLeft(0){ _ + _ } == fiveTimesThree.foldLeft(0){ _ + _ }

// res: Boolean = true

Now we can ask other questions, using non-standard interpretations, showing other differences between these expressions. For example, lets ask how many operations each expression requires. It’s simple to write this interpretation using our list representation.

def numberOfOperations(expression: List[Int]): Int =

expression.length - 1

numberOfOperations(threeTimesFive)

// res: Int = 2

numberOfOperations(fiveTimesThree)

// res: Int = 4

Clearly they aren’t equivalent under this interpretation. What else can we do? Well, perhaps when we wrote 5+5 we actually meant to use Tropical numbers. Tropical numbers, and associated tropical geometry, is a fairly new branch of mathematics with connections to optimisation problems. Tropical numbers are defined so + means min. With our list representation it is no problem to implement this alternative interpretation.

def tropicalEval(expression: List[Int]): Int =

expression.foldLeft(expression.head){ _ min _ }

tropicalEval(threeTimesFive)

// res: Int = 5

tropicalEval(fiveTimesThree)

// res: Int = 3

Once again we’ve seen a non-standard interpretation under which the two expressions are not equivalent.

Regular readers of this blog will recognise that we’re employing one of our favourite tricks: separating the description of the computation from the process that gives it meaning. (See here and here, for example.) Our list of integers is the abstract syntax tree (AST), and the different interpretations are interpreters for that AST.

How did we know we could use a List to represent our AST? We’re implicitly making use of a few facts about addition. First that it is associative, which means that (5 + 5) + 5 is the same as 5 + (5 + 5). This means it doesn’t matter where we place the brackets so we can choose one canonical bracketing that corresponds to our list structure. We are also assuming we have an identity element that is equivalent to the empty list. In other words we’re assuming a monoid and using the free monoid representation.

Can we leverage any other properties? Multiplication is also commutative, meaning x*y is equivalent (under the standard interpretation) to y*x. We can use this to transform one list to another with lower runtime cost.

def optimise(expression: List[Int]): List[Int] = {

val value = expression.head

val ops = numberOfOperations(expression)

if(value < ops)

List.fill(value){ ops + 1 }

else

expression

}

optimise(threeTimesFive)

// res: List[Int] = List(5, 5, 5)

optimise(fiveTimesThree)

// res: List[Int] = List(5, 5, 5)

This is why we care about laws for our type classes. They tell us what transformations are legal.

So the teacher is correct. 3×5 is not equal to 5×3, but under the standard interpretation they are equivalent. There is some deep stuff going on here. I’m not equipped to say if this is appropriate to teach children, but if it works it’s awesome stuff. Maths is not about calculating but about manipulating abstract structure, and if the students are being taught that it seems to me to be a good thing. And it’s entirely possible that this example will have given some adults, including me, a deeper appreciation of the depth of structure in simple arithmetic expressions.